ITALY 19th century

For us to understand the family history and the reason for the grand emigration of the Italians in the 1880s we must try to understand what was happening, or had happened in Italy in the 1860s.

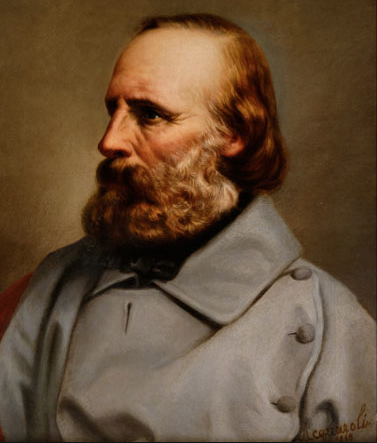

Giuseppe Garibaldi was born on the 4th of July in the year 1807 in the city of Nice, France, commonly called Nizza in Italian. By his twenties he joined the Carbonari Italian Patriot Revelotionaries and he had to flee Italy after a failed insurrection. By the year 1832 he participated actively in the Nizzardo Italian movement and went on to become a Captain in the Merchant Navy.

Throughout his revolutionary movements and naval escapades over the next thirty years he was responsible for the unification of Italy and even challenged the great Rome itself. He is now a national hero, but at that time the regions were in great crisis.

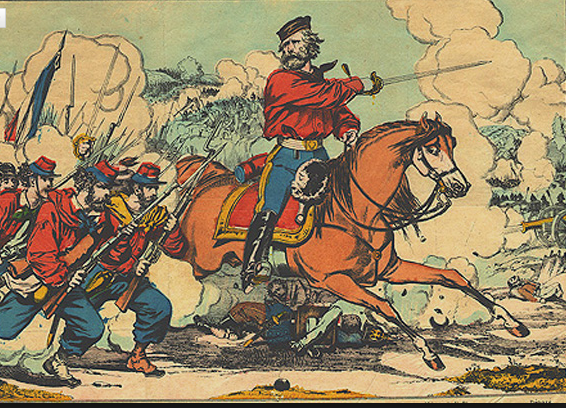

As every schoolboy used to know Garibaldi was the chap who marched up and down Italy with 1000 men in red shirts fighting everybody who was against the unification of Italy. He was the original action hero, a revolutionary, a sex symbol of the time, a global celebrity, having travelled the globe in his role as a Merchant Seaman Captain.

This handsome swashbuckler with long hair, full beard, burning eyes and his trademark red cape, cut a swathe through European politics during the mid 19th century. For three decades Garibaldi took part in every major battle in Italy, provoking revolution in Sicily, bringing about the collapse of the Bourbon Monarchy, the retreat of the Austrian Empire and the overthrow of the Papal States and the creation of the Italian nation. At one point the reigning pope put a large bounty on his head, but, no one in the Italian provinces betrayed him.

The high point of his reputation came with that infamous invasion of Sicily. He then proceeded to the mainland of Italy. First he crushed the Neapolitan army, then travelling at an incredible speed he bypassed the formidable Neapolitan Navy, which was the largest in the Mediterranean. He proceeded into the mainland and swept 300 miles north towards Naples. The population lined the roads as he passed calling him the Father of Italy and the women brought out their babies to be blessed as he passed by.

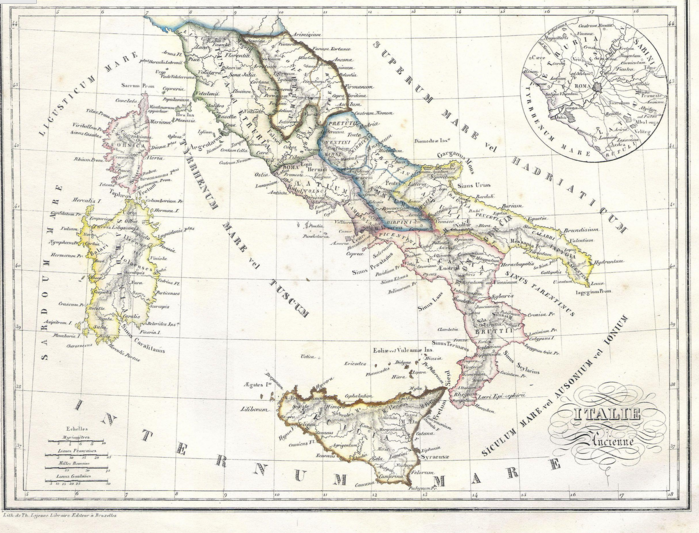

Italy remained a patchwork of small states after the post-Napoleonic settlement of Europe in 1815, which gave back the Papal States to the pope and restored the House of Savoy to the kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia and a branch of the Bourbons to the Two Sicilies (Naples and Sicily). The Austrian Habsburgs took control of Lombardy, Venice and other cities in the north, but an Italian drive for unity and freedom from foreign control would eventually prove irresistible.

The great hero of the struggle, Giuseppe Garibaldi, aroused as much alarm in the breasts of its principal beneficiaries as he did in his enemies. He was feared as a human hurricane who might destroy everything in his path. To make it worse, he was hugely popular. It was Garibaldi who made Victor Emmanuel II of Piedmont the ruler of a united Italy, while the king stood ever ready to disavow him.

Born in 1806 and a sea captain in his youth, Garibaldi spent from 1834 to 1848 exiled in South America where he fought in various liberation struggles and mastered the techniques of guerrilla warfare that he later deployed so effectively in Sicily and Italy. For the rest of his life he swaggered about in the gaucho costume of a South American cowboy. Returning to Europe, in 1849 he commanded a brilliant, if doomed, defence of Rome against the French, but was forced abroad again. From 1854 he settled to farming on the island of Caprera, off Sardinia.

But in April 1860 a rebellion erupted in Sicily and Garibaldi seized the opportunity, sailing from Genoa with a force of volunteers known as ‘the Thousand’ or ‘the Red Shirts’ in two steamships. Victor Emmanuel and his chief minister, Count Camillo Cavour, had agreed to back him if he was successful, on the understanding that they would deny any connection with him if he failed.

With help from Royal Navy vessels, Garibaldi and his men landed at Marsala on Sicily’s west coast on May 11th. They quickly took the town and assembled the town council, which declared Bourbon rule of Sicily at an end and called on Garibaldi to take over as dictator in the name of King Victor Emmanuel. Garibaldi accepted. Joined by hundreds of Sicilian rebels – many of whom contented themselves with firing their guns in the air and bellowing rather than actually fighting – he led his army towards Palermo. There was a battle at Calatafimi, where Garibaldi reportedly said ‘Here we make Italy or die’ and the Garibaldini put superior numbers of regular Neapolitan troops to flight. The victory sparked a powerful surge of Sicilian support for the invaders, who pressed on to the Sicilian capital.

Forcing a gate in the early hours of May 27th, the Garibaldini swarmed in. The population rose in support and fierce fighting raged in the streets. Garibaldi organised a committee of leading citizens to run the city, while he himself deliberately spent much of his time receiving messages and issuing his orders from a command post beside the grand Renaissance fountain in the central square, the Piazza Pretorio, where he was a target for repeated enemy fire. Many of the townspeople thought the little whip he casually twirled in his hand miraculously kept him safe. The effect on his supporters’ morale was exactly as he had calculated.

The Neapolitan garrison under the elderly and entirely outclassed General Ferdinando Lanza was gradually confined mainly to the area round the Royal Palace. By May 29th the palace itself was threatened and on the 30th Lanza sent a message to Garibaldi suggesting a parley. Garibaldi, who was now almost out of ammunition, gladly arranged for a brief armistice and a conference to begin at noon. The armistice was prolonged while Lanza worried and hesitated over what to do until at last on June 6th he capitulated and the Neapolitans marched out the next day with full military honours.

The seizure of Palermo confirmed Victor Emmanuel and Cavour in their decision to back Garibaldi. He moved eastwards across Sicily and took Messina, crossed to Calabria in mid-August and drove on to Naples, which he entered on September 7th. Cavour was now using the threat of a takeover by Garibaldi to persuade the European powers to back Victor Emmanuel. The Piedmontese army had already invaded and annexed the Papal States. The following month, October, Garibaldi organised a plebiscite that by a predictably gigantic majority handed Naples and Sicily over to Victor Emmanuel. Refusing all rewards, Garibaldi withdrew to the background and Victor Emmanuel was proclaimed King of Italy by the new Italian parliament in March 1861.

Garibaldi led occasional campaigns for Victor Emmanuel up to 1871, but then retired to Caprera. Crippled by wounds and rheumatism, he died there in 1882 at the age of 74.

The Quilietti were one of the first of the Northern Italians to leave for a new life. The little hamlet of Castelvecchio, later known as Castelvecchio Pascoli, Barga, Toscana, Italy, was the home of the Quilietti family at this turbulant time.

Our Maternal family also left from the homeland in the Province of Parma. They travelled through France and some of the Brattisani clan still live there today.

Other branches of the family left for America.

In 1871 an attempt was made to survey the Italians who were abroad, gathering the data provided by consulates in places of arrival, you do not succeed, however, to collect all necessary data, among others, those relating to the United States failed.

Parma was the Emilian province in which the phenomenon took on higher values.According to the Census, migration Parma was heading first to France and its colonies; alone received more than 55% of our emigrants, they are directed mainly towards Corsica, and then, all along the country’s eastern Alps , Marseille and Nice to Paris and Lille.

In second place, but far away from France, there was Britain, where our emigrants were concentrated mainly in London, followed two South American countries, Argentina and Uruguay, then Switzerland (especially the Canton Ticino).

The turkish empire for over 100 Parma, scattered, however, from Alexandria and Cairo in Egypt (the Suez Canal was opened in late 1869 and in Egypt there was great animation), in Istanbul, Bucharest, etc..

A significant number was in Russia, the three “poles” of Odessa, Moscow and St. Petersburg, while in Germany, our migrants were scattered in different areas of that country, in Spain were mainly present in Catalonia.

In the period 1876-1920, the province of Parma was composed of three “districts” that included the following municipalities:

Districts Borgotaro: Albanvale, Bedonia, Berceto, Borgotaro Compiano, Tornolo, Valmozzola

Leave a Reply