BARGA – The ROOTS

http://www.bargainfotografia.com/facebook.html?fbclid=IwAR2xjFBGzmsGInLeyVQQr4-UD8DrfOE5AdTzLlFo4JSJKJIU-HbudyfDiDU

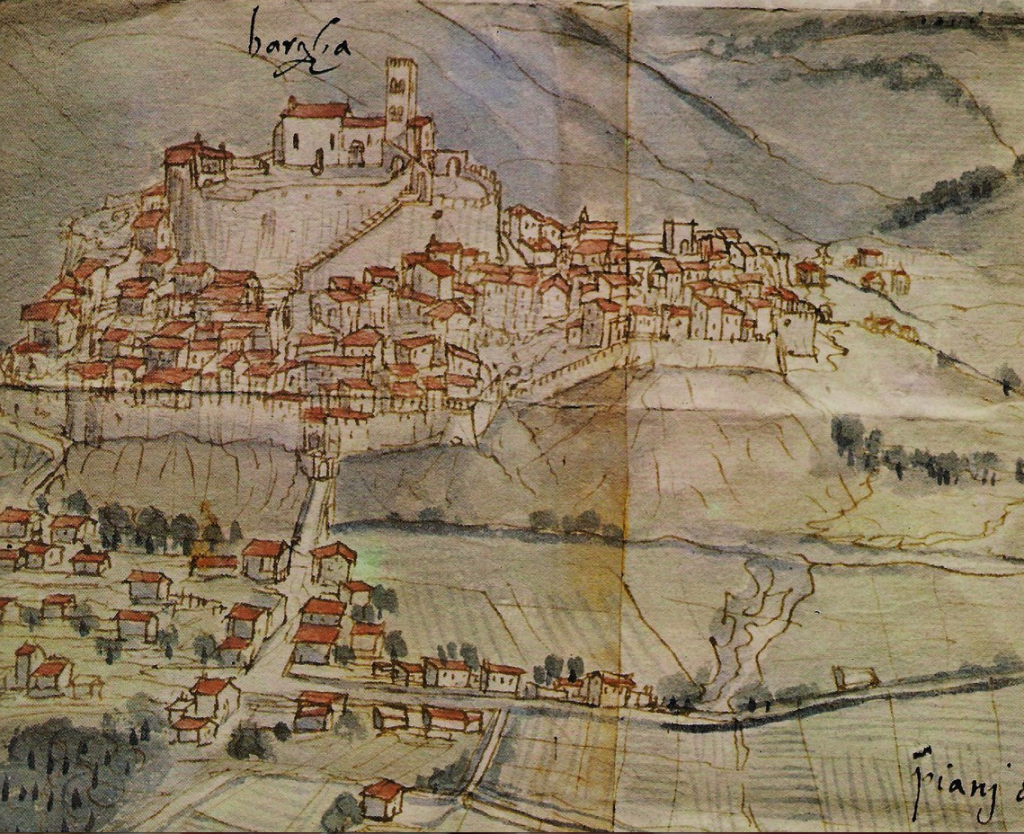

an old map of Barga 1650

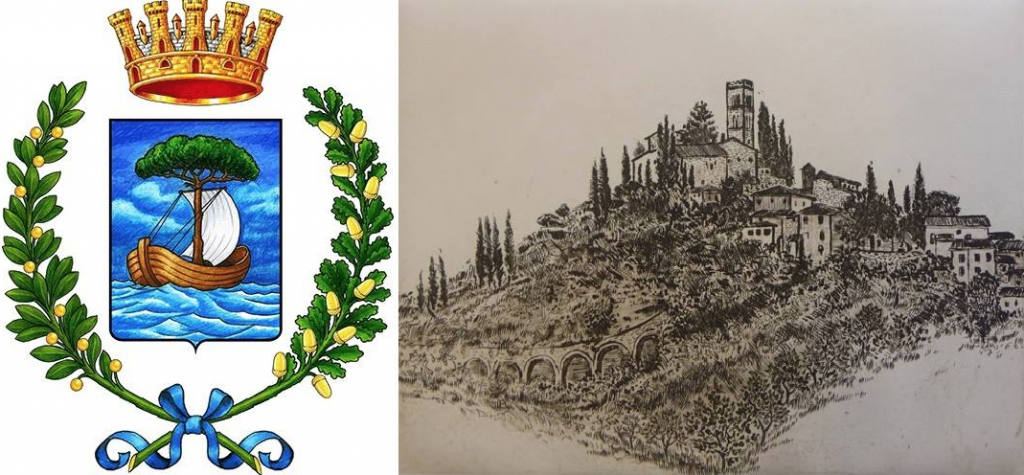

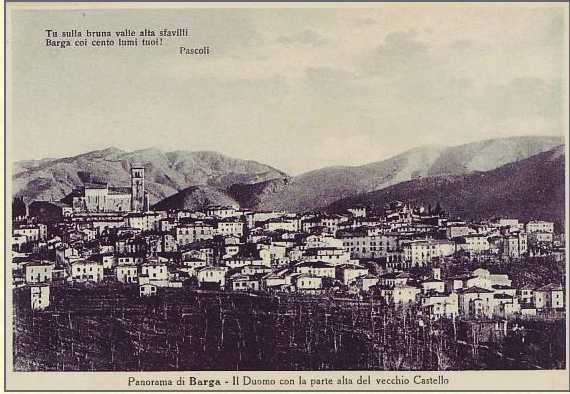

The village of Barga in northern Tuscany claims with some merit to be one of I Borghi Piu belli d?Italia. Standing on a wooded hill above the valley of the Serchio River, the walled settlement with its twisting flagged streets and grand Palazzi is a time capsule of centuries-ago Italy, and a more beautiful town would be hard to find.

However Barga’s second claim to fame is true beyond doubt, it is certainly Il Borgho piu Scozzese d’Italia, and the nearest thing Scotland has had to a colony, due to its connections with the Italian community in Scotland. This combination of Italian exoticism underlain with Scots familiarity alone would make this a unique and fascinating place.

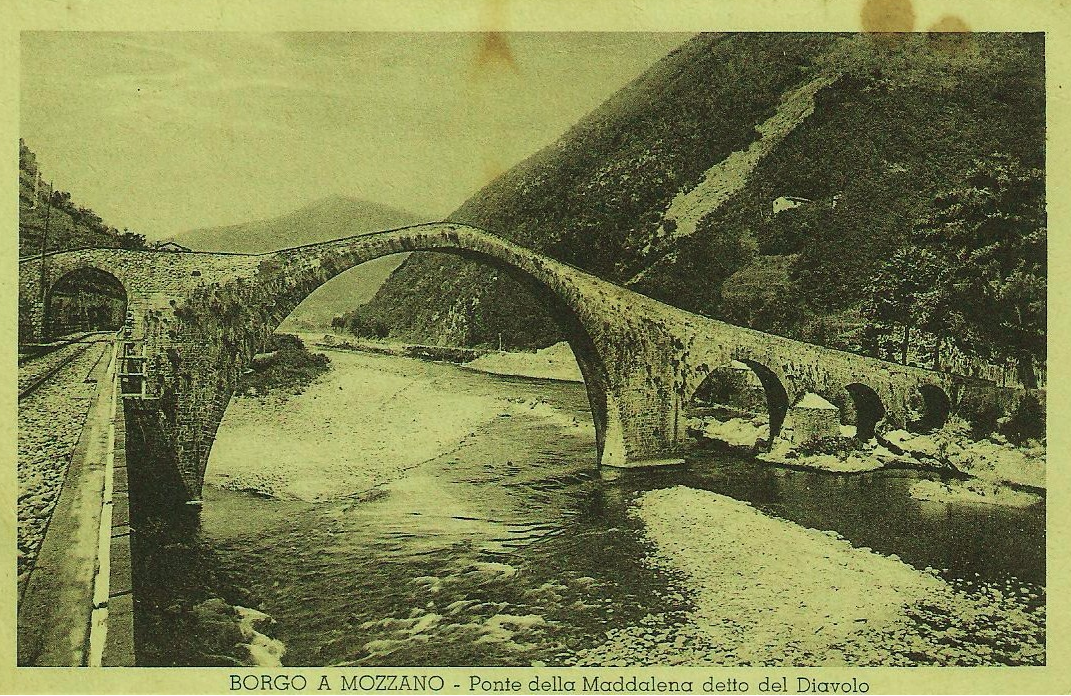

Lying in the province of Lucca, Barga has been an important place since the construction of its cathedral in the 10th. century. Coming under the dominance of Lucca, then Florence, Barga prospered through trade and eventually became integrated into the united Italy created in 1861.

Barga itself had a colourful past with its strategic position high in the mountains there was always many conflicts trying to take over. Lucca and Pisa were continually trying to take over but Barga was always faithful to Florence and the Medici influences there. The territory gained many exemptions from taxes over their five century union with Florence which included exemptions from Contract Tax, Milling Tax, Salt sub-charges, livestock tax, and many more including exemption from tax on playing cards, straw hats, tobacco and wine!! The deep relationship between Florence and Barga remain in the former’s art, religion, customs and language.

Many famous architects and artists were in the employ of the Grand Duchy and they left their mark on many ancient churches. Monesteries were embellished with luminous teracotta work.

From about 1500 landowners invested their capital in the construction of silk factories, grain mills, presses and paper mills, exploiting the waters of the torrents of the River Serchio.

The Unification of Italy resulted in serious economic damage not only in the Barga region, but all over the new country. The wealthy landowners were now burdened with taxes imposed by the Napoleonic government of the past fifty years. This state of depression led to the great emigration of the time.

The Barga figurine makers who in the first half of the 19th century had headed to France, Austria, Germany and Russia now found their way in great masses to the United States and also Scotland.

However by this time its former glories had gone, and like much of Tuscany and Italy in general, Barga’s main product was that of emigrants seeking to escape from the poverty associated with working small plots of land under conditions of feudal exploitation. Successful emigrants started as street traders and worked themselves up to owners of groceries, barbers’ shops and restaurants, attracting fellows from their local village

Some Tuscan villages organised a trail to America, some to Argentina, but from Barga, as luck would have it, the trail led to Scotland. Today the wealth gained from emigrants has helped transform Barga. But the links remain; each summer the town is full of Scots-Italians.

Barga herself has three main gates The Porta Macchiaia, Porta Reale or Mancianella and Porta di Borga. Porta Reale is the most important and was restored in 1894. Just outside her walls are three satellite districts, Fornacetta, Giardino and Frati. They were populated by farm labourers, craftsmen and a few small landowners.

The Italians who came to Scotland brought our country great benefits, like cappuccino, spaghetti and good ice-cream, but they kept the best to themselves, as a trip to Barga will demonstrate. Many of the restaurants there belong to families who have establishments in Dumfries, Paisley, Edinburgh , Aberdeen, and as far north as Inverness and beyond.

But gastronomic standards here are far higher- and prices far lower, than in Scotland. This is Chianti country and as well as names of those denominazioni you will have heard of at home for a fraction of the price, most restaurants and the local alimentari sell local wines produced in small quantities, often from the booming organic wine producing sector. Wine tasting tours are available, and allow the sampling of several wines by small local producers, with the opportunities to purchase, and include a gastronomic lunch.

The food is superb. The hills north of Lucca produce probably the best olive oil in the world, in a bewildering array of varieties, and the woods are the source of the abundant porcini which feature in many local dishes. Buy these mushrooms in local shops and they will cost a fraction of what they will back at the airport. But of course Olive Oil Producers from the south in Puglia and Sicily would argue that their produce is the best.

The woods are also full of castagni, local chestnuts which feature in many dishes and are also ground into flour for baking, producing excellent crepes and torte. Chestnut flour is also used as the basis of the local polenta which features prominently in the cooking. Other items on the menu are trout from the Serchio River, and wild boar from the woods of the hills around the village. Ice cream comes in every conceivable variety, including that made with local frutta di bosco, and most deliciously, one version that looked like it was made with peas, but which turned out to be a delicious sour-apple ice cream.

For a small town, Barga buzzes. In July there takes place the festival of Barga Jazz, where local musicians perform in the open air in the evenings, and you can eat you meal al fresco to a musical accompaniment. The town has always attracted artists and writers, such as the great poet Giovanni Pascoli who made the town his home a century ago, and died there, in what he called “the land of the beautiful and the good.

You can sit on the balcony at the Caffe Capretz, one of his favourite spots, and look over the flowers on the railings at the Apuane mountains. The composer Puccini was a friend of Pascoli and a regular visitor to Barga and a whole host of artists known as the Pascoli Generation found inspiration in the town, such as Cordati, Magri and Santini.

It is the nearby village of Castelvecchio Pascoli where our Quilietti roots lie. But there are other small villages with much history attached also. There is the village of Tiglio which is close enough to walk to and it has spectacular views of Barga herself. There is also the village of Lopia which is within walking distance but through a more complicated route. Barga also has wonderful markets. Every Saturday morning the stalls set up around the New Town Area. They sell everything from fresh produce, clothing, shoes and plants and flowers.

At the time of the Unification of Italy there was great upheaval in the new country. The land surrounding Barga was taken over by the rich and they rented out crofts to the families who lived on the land. It was mountainous country often 900 – 1000 metres or so above sea level. Crops could not grow easily that high and grapes and olives would struggle to survive. . The bigger the family, the bigger was the croft offered. This meant that for everyone in the family, no matter how old or how young, they were expected to work on the land. The land could be made to produce more for the owner of the land. These sharecroppers were known as Mezzsadri from the word mezzo [half] . The rental paid to the landowner was not in cash, but consisted of one half of everything, the land, the sheep, the milk products and if the croft was big enough to sustain more that just a few sheep then they would have to hand over half of the wool provided from the sheep. These were hard times indeed. The landowner would hire men to go around his estates with trains of mules as there were no roads up the mountains in those days. to collect his share of the produce. Whatever remained was for the family to live on. They existed on what they produced and barter was a common form of trading. If one small hamlet village had excess cheese then they would trade with another who had a surplus of whatever. There would be no cash involved. It would only be when you arrived in Barga itself to the local market that you could obtain cash for any produce you had to sell. The lack of roads however made the transportation of farm produce a daunting proposition. The roads would often have rocky dangerous paths and would not be easily manouvered.

Chestnuts would also provide another source of food and over the winter months old trees would be felled and the trunk and branches cut into logs and charred over open fires. The charred logs were then tied into bundles and sent to the valley below by means of primitive one-way funicular cables there to be sold as firewood.

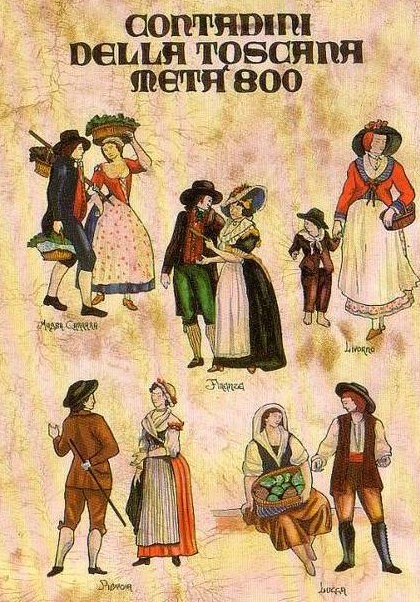

This had been the way of life in the hills above Barga for centuries and was the way of life for thousands of peasant families in the hills of Tuscany. This way of offered no hope for the children of these peasant families there seemed no way out

This way of life would certainly have contributed to the ass immigration of the Tuscan children and certainly contributed in our own family’s mass emigration to Scotland and the New World

Once a month there is also a market in the Old Town where stalls are set up in all sorts of nooks and crannies for you to enjoy

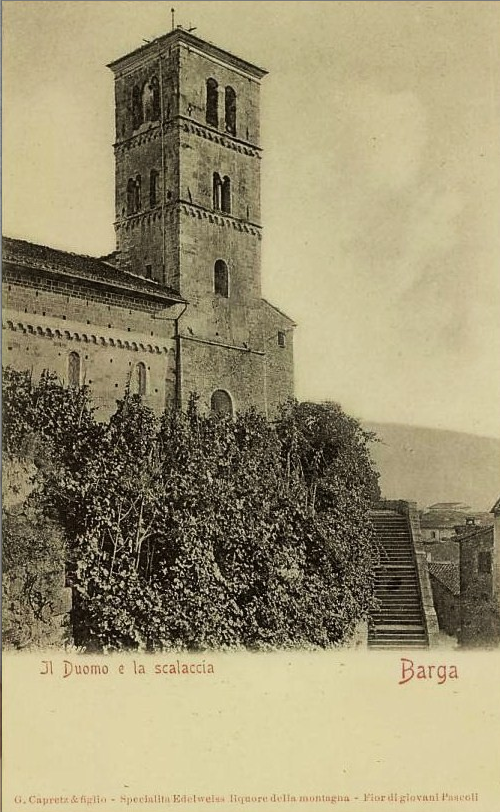

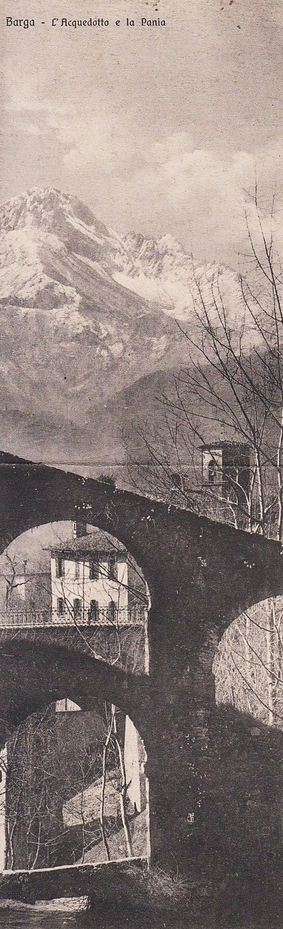

Barga’s shadowy passages are good to explore and if you climb high enough there is a broad flight of stairs which lead you up to the Duomo. From this vantage point you can look down on the rooftops below and beyond them and across the valley of the Apuan Mountainsa and in particular the White planed summit called Monte Pania della Croce. The white snowy top never seems to leave her high peaks. But of course it does snow in Barga as the photograph above shows and also the photos here as shown in utube

If you are of Northern Italian descent and have never visited Barga, then you have a wonderful surprise awaiting you.

Dear sir My grandmother died recently and I was wondering if you have heard of her side of the Donati line. She came to Scotland from Boston Massecheusetts where she was born with her father and two sisters in early 1900,s. Her father died early at 28 years old and she was left with her two sisters Liza and Linda. her own name was Eida Tognieri Donati born 11th August 1913 and died 27th December 2010 age 97 years. She was married to my grandfather Archibald Thomas Galbraith. Any information would be greatly appreciated if possilble. Thank you Alexander Campbell Galbraith

I will check through my files. Do remember the Tognieri name but think it is through another branch of the family. Helen

Hi there, can you let me search through my files and get back to you. I have a bit of information on our branch of the Donati line but could you let me know what kind of information you are looking for

Thanks Helen. I was wondering if you could provide any information on he Togneri line as this is my grandmothers line and it would also help me with my research as I am finding it very difficult because of the ages and the spread of my grandmothers family also in America. Thank you

info eida galbraith father sabatino donati lived florence st boston mass, 1913 lobster cutter

eida mria togneri donati had also a brother amerigo who died circa aged 2 in a fire aiso last remaining relative died 20 plus years ago in barga name ottavia badiali